Fourth in the Helping Dad series

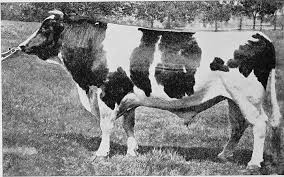

Dad was a dairy farmer with a herd of Holsteins, the black and white spotted cattle that seem to be the example of how a cow should look. The breed is called Holstein in the United States, while you might hear Friesian for the same cattle in the United Kingdom. They are hardy animals, big and tall, the biggest breed of dairy cows. The big cows are big milk producers.

Dad grew up on dairy farms. He helped his father from a young age and chose the lifestyle for himself. Dad was an animal lover and he cared for every cow. He knew them and had names for many of them.

Dad maintained about 80 head of cattle on the farm. After buying his first herd in 1966, all the other dairy cattle were born and raised on the farm. Dad kept his herd numbers constant by raising female calves. On any given day, Dad milked almost half of the herd twice daily. The other 40 needed food, water, and care but did not produce. Accidents and illnesses happen, no matter what, so the extra cows were needed.

About half of the non-milkers were baby cows called calves, or heifers, the term for young cows. They were too young to produce milk. The other 20 cows were mature enough but had no milk to give. They were “dry cows”. A cow must give birth to produce milk like every other mammal. The dry cows had stopped making milk. Some of them might be pregnant. Others might be resting and not yet ready to breed.

To have milk, you need to have calves. To make calves, a bull is required. There is a proven method to produce calves from a bull that is not on-site. That would be artificial insemination. Dad used this program for a time, but he eventually decided to keep a bull in the herd.

Dad owned bulls several over the 20 years he had the dairy. Bulls are generally larger than cows, and a full-grown Holstein bull can be huge. When they reach maturity, they might weigh as much as 2,000 pounds and stand over five and a half feet tall at the shoulder.

I knew of tame bulls, but they were not dairy bulls. Some bulls came to the farm with good temperaments like the one in this story. By age five or six, our bulls were huge and ill-tempered. When Dad got this bull, he was young but old enough to do his job. His temperament was no worse than the cows in his herd.

A blog article I read recently had some interesting points about why dairy bulls are meaner than beef bulls. The link is on the blog’s home page. The aggression was true for Dad’s bulls. He had dairy cows for 20 years and beef for another 15 years. The dairy bulls were meaner, more aggressive.

Dad’s Holstein bulls also got meaner with age. This phenomenon is discussed in the blog article and happens with many dairy bulls. Dad kept a bull for no more than four years. He did not want inbred cattle, from the bull fathering calves with his daughters.

Even a tame bull can be dangerous because of its size. They can crush you up against a wall or a fence without noticing you were there.

Vigilance is essential when you are on foot in a pasture with cows. Cows are big animals, too. They weigh up to 1,500 pounds and stand as tall as five feet. Cows are curious; some may come up to you to see what you are doing. A few of Dad’s cows would let you stroke their heads. Bulls will act to keep their herd together and under their protection. They might view your presence as a threat. You must be even more cautious when a bull is in the herd,

This bull didn’t mind going through fences. Cattle may nibble trees, grass, and weeds that poke through the fence finding weak points by accident. The young bull had two or three methods to get to the greener grass on the other side of the fence. He could push at a sagging fence until it stretched enough to walk across. He could break a fence post if it seemed a little weak to let the fence down that way. Or he would push through a spot in the fence that needed repair. It was good that this bull was still docile because Dad had to find him and bring him back more than once.

One summer day, Dad announced that he needed my and my sister’s help. I was about 12 or thirteen; my sister would have been no more than eight. We followed him outside, wanting to know what we were doing. We got into his pickup truck, and he said we were going to get the bull back from a neighbor’s farm. This neighbor raised beef cattle and would not think kindly of us if all his calves were white with black spots.

I had a question, why did Dad need my sister and me? It sounded like a solo project to me. Dad said we had to go by fields with no gates and fences that needed mending. The cattle were not grazing there, so the fences and gates had low priority. He did not want to chase the bull out of those fields or take the chance that he would be able to escape somewhere else.

The next question from me was not a question. “We….. are going to get the bull???” “Yes”, Dad said. “I will put each of you where the bull might try to go. When he comes towards you, wave your arms and yell.” He said it like he was taking us to get a kitten.

“Where will you be, Dad?” He was going to be in the pickup truck, herding the bull. He would pick us up after the bull passed the opening we were guarding. The animal moved too fast to do it on foot.

My sister and I were concerned, but Dad wouldn’t have us here if the bull would run us over. So we got out of the truck in two different spots: my sister and then me. I would be the first to face the bull. Dad’s pickup went out of sight, and we waited. It seemed like hours.

My overactive imagination took me to places I didn’t want to go. I pictured the bull running by me to toss my sister in the air. Then he turned and ran over to my spot with spittle flying and wild eyes, pawing the ground with a front foot. Where would I go? He can go through fences, that much we knew. There was nothing but fence posts to get behind or climb on.

I heard the truck engine, and I steeled myself. The bull and the pickup truck came over the rise in the pasture, the bull going at a trot. Dad was pacing him to keep him moving forward, so the bull didn’t have much time for ideas about finding other pastures.

As they got closer, I made myself as big as possible and waved my arms. I shouted, “Hey, hey,” as the bull went by. He barely looked in my direction. Dad slammed the truck to a stop and yelled for me to get in fast. He didn’t have to say it twice. He jerked the truck into gear and raced to where my sister stood. The bull passed her, not even turning his head.

There were several fields still between us and the barn. With my sister on board, Dad sped back to the bull. He began to honk the horn to keep him trotting and moving. He used the pickup as a tool to herd the bull in one direction or the other. The truck made contact with the bull accidentally a couple of times. The bull did not act as if it noticed. I was so relieved to be in the truck. I had accomplished something scary, so I was proud too.

Dad speeded up as the bull began to veer off. We pulled along its left side while Dad honked again so the bull would turn to the right. The bull took his huge, hornless head and slammed it into the pickup at the front passenger side fender. The truck jumped from the impact, but Dad had it under control.

My sister and I looked at each other, wide-eyed and mouths open. We felt as if we had dodged a bullet in a manner of speaking. It wasn’t really a bullet. It was a bull.

Dad backed off, giving the bull a little space. The bull trotted back the rest of the way to the barn lot. After a few maneuvers with gates, keeping the bull in and us out, the bull was in the proper pasture. Dad checked the truck fender for a dent. He didn’t find one, but there was a spot that was flatter than before.

Dad headed for the house. My sister and I were still unusually quiet, doing none of the things little girls always do in a vehicle, like giggling, bouncing, and singing. In the kitchen, Mom asked if the bull was back home. Dad, sister, and I said yes in unison. “Any problems?” she asked. Dad answered, a little slower than usual, “Naw, nothing worth telling.”